What is the “Desirable Difficulty Principle?”(and 4 fun ways to integrate it in your language learning classroom!)

Do you feel uncomfortable watching your students struggle in the target language? You shouldn’t! Read to find out why.

Guten Tag! Mno waben! Welcome back, language teachers, to Adventures in Language. In this article, we’re talking about the “Desirable Difficulty” Principle — what it is, why it matters, and 4 fun ways you can incorporate it into your language classroom! The main takeaway is this: research suggests that struggling is often what active learning can look like – and it’s not something teachers should automatically shy away from. If you want to learn more, then keep reading. Well, 前置きはさておき(‘without further ado’ in Japanese), let’s get to it!

So, what is the Desirable Difficulty Principle?

It’s basically psychology’s jargony way to say “no pain no gain.” It’s the idea that certain types of intellectual discomfort can actually be productive for the learning process. The takeaway there for teachers? Help your students embrace (not avoid) the struggles of learning! Psychology research dating back to the mid-90s has been consistently demonstrating that forcing our brains to work harder will result in better learning outcomes — specifically, in terms of memory storage and memory retrieval. Put another way, activities that require extra cognitive effort — or extra difficulty — can facilitate learning — thus, are deemed desirable. For those of you in the know, you may be wondering “Is this similar to Krashen’s “i +1” Hypothesis?” If so – you’re right! It is similar. Krashen’s i + 1 is one of many ways to incorporate desirable difficulties into your students’ language learning process. We can’t dive into Krashen today, but we absolutely must give a shout-out to Dr. Elizabeth and Dr. Robert Bjork, two cognitive psychology researchers based out of UCLA who pioneered the academic research on desirable difficulties. The scholarly work of this famous power couple has paved the way for the development of more effective teaching methodologies, which have served to enhance language education. If you’d like to explore more about their break-through research into the Desirable Difficulty Principle or how it relates specifically to Second Language Acquisition, check out the papers we’ve linked for you at the end of this article.

How can language teachers make use of it?

There are infinite ways to incorporate desirable difficulties into your language classroom, and we invite you to have fun trying out some new ones with your students. To get you started, we’re going to share with you 4 of our favorite go-to strategies:

Sprinkling in error-based learning activities

Practicing old content in new contexts

Avoiding the tendency to oversimplify your speech

Get your students access to the Mango app!

Now let’s break those strategies down one at a time…

1. Sprinkle in error-based learning activities

Error-based learning activities are activities designed to help students discover common mistakes in the target language. One fun way to do this is to start every class off with a “Catch the Error” warm-up prompt. Find a paragraph in the target language and plant a common error in it. For example, since English learners of Spanish often incorrectly assume the word embarazada means ‘embarrassed’ (it actually means pregnant), a Spanish teacher might plant the incorrect word in a “Catch the Error” prompt. This task can be quite challenging for students, but that’s the point. It requires them to build their metacognitive skills by engaging in error-monitoring in the target language. And don’t limit yourself to written prompts: have fun with auditory ones as well to help your students practice their listening skills. Important: don’t include just any random errors. Rather, strategically identify errors that you have seen cropping up in their work lately, mistakes that are common for learners of their source language, or tricky L2 rule exceptions that you want them to know about (e.g. an irregular verb conjugation they haven’t been formally taught yet). We also suggest telling students at the beginning of the semester that you’re going to use error-based learning strategies like these. This can be a good idea because some students may think you’re using strategies like this to trick them. On the contrary, you’re doing it because it works and it’s effective for their learning.

2. Practice old content in new contexts

Oftentimes, language learning curricula will associate a grammatical concept with a consistent context. For example, verbal commands get taught in the context of chores. Telling time is taught in the context of daily routines. But spicing up that learning content in new contexts actually helps boost memory recall in the brain — because it’s a desirable difficulty. So, have your students practice verbal commands in the context of a social media post. Or do an in-class activity where they practice telling time by re-telling the plot of a movie. Simply put, you can provide your students with opportunities for desirable difficulty by encouraging them to form new associations and connections in memory with the learning material.

3. Avoid the tendency to oversimplify your speech

Many teachers have the tendency to simplify their speech in the target language to match their students’ proficiency level. Now, this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It stems from a good pedagogical intuition to “meet the learners where they are,” and it can be a successful input strategy. But not in excess. If you oversimplify your speech, you might be putting your students at a disadvantage, by stunting or stalling their progress in the target language. So, in order to not miss out on some great opportunities to present desirable difficulty in new vocabulary and innovative grammatical structures, try to aim your speech for just above the level your students are currently at (which is what Krashen’s i + 1 hypothesis would recommend).

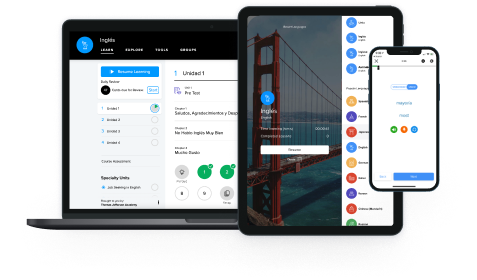

4. Get your students access to the Mango Languages app!

Why? Because the lesson sequences within the Mango app were actually built with desirable difficulties in mind. For example, if you were to take the Mandarin course within the app, you’d start off by learning the word for good (which is 好[hăo]) and the word for morning (which is 早上[zăoshàng]). And then we ask you to guess how you’d construct the phrase ‘good morning.’ Now, most English speakers would order the words as they are in English. So, they are likely to say hăo zăoshàng – literally good [pause] morning.’ But the Mandarin word order is flipped, so the correct way to say this would be ‘morning good’ – or zăoshàng hăo. The app predicts this response and follows up with a reassuring note to help the student solidify this concept in their memory. Long story short, the app has been designed in such a way that you’ll easily and seamlessly learn these idiosyncratic patterns, irregularities and gems in a way that’s optimally efficient! For more information about how the Mango app is structured in line with the other principles from Second Language Acquisition research, head to the bottom of the article to get a free copy of this info pack, which highlights the app’s primary features. BONUS: clicking that link will also get you a FREE fun, goal-setting worksheet that you can use with your students (which they’re going to love!).

Quick recap!

Here are the two main takeaways should you be leaving with:

Desirable difficulties promote positive learning outcomes.

Of the many teaching strategies that you can use to incorporate desirable difficulties into your classroom, we mentioned these four: (1) sprinkling in error-based learning tasks (2) practicing old content in new contexts and (3) avoiding the tendency to oversimplify your speech, and (4) encouraging your students to use the Mango app outside of class!

Thanks for reading!

Now that you’ve finished the article, we hope you remember that struggling and stumbling aren’t always signs of failure for your students. That can be the Desirable Difficulty Principle at work, helping the target language ‘stick’ for your students. Well, language teachers – Auf Wiedersehen! Gwi wabmenëm! We look forward to seeing you back here for our next article.

Wondering what languages were used in this article?

English | Recording language

German | Guten Tag and Auf Wiedersehen are ‘hello’ and ‘goodbye.’

Potawatomi | Mno waben and gwi wabmenëm are ‘good morning’ and ‘I will see you’ in Potawatomi, which is an Algonquin language spoken in the Great Lakes and Great Plains region. Did you know – there is no word for ‘goodbye’ in Potawatomi? This is because Potawatomi believe that we’ll always see each other in another time and place, both physically and spiritually.

Japanese | 前置きはさておき[maeoki-wa sate oki] means ‘without further ado’ (literally translates as ‘setting aside introductory remarks’).

Mandarin Chinese | 早上 好[zăoshàng hăo] means ‘good morning’ (literally translates as ‘morning good’).

Want to know more about the scientific research underlying this article?

For a nice overview of the principle: Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (2020). Desirable difficulties in theory and practice. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 9(4), 475-479 or

To explore some little-known caveats: McDaniel, M. A., & Butler, A. C. (2011). A contextual framework for understanding when difficulties are desirable. Successful remembering and successful forgetting: A festschrift in honor of Robert A. Bjork, 175-198.

For specifics into language pedagogy: Suzuki, Y., Nakata, T., & Dekeyser, R. (2019). The desirable difficulty framework as a theoretical foundation for optimizing and researching second language practice. The Modern Language Journal, 103(3), 713-720.

To zoom in on vocabulary learning: Bjork, R. A., & Kroll, J. F. (2015). Desirable difficulties in vocabulary learning. The American journal of psychology, 128(2), 241.

And remember – language teaching is an adventure. Enjoy the ride!

Mango For EducationDownloadable Resources

Elevate your language-learning journey to new heights with the following downloadable resources.